The typical pharmaceutical business is far more complex today than in the industry’s blockbuster era, when fewer products, more stable demand, and high margins were the norm. For pharma companies to meet the growing complexity of the industry and the varying demands of their business segments, they need supply chain models that support the strategic priorities—agility, service, or cost effectiveness—of those different segments. A recent benchmarking study by The Boston Consulting Group identified four supply-chain models that can lead to optimal performance. This segmented approach to supply chain design is becoming the most effective way for pharma companies to address the challenges and tradeoffs they face today.

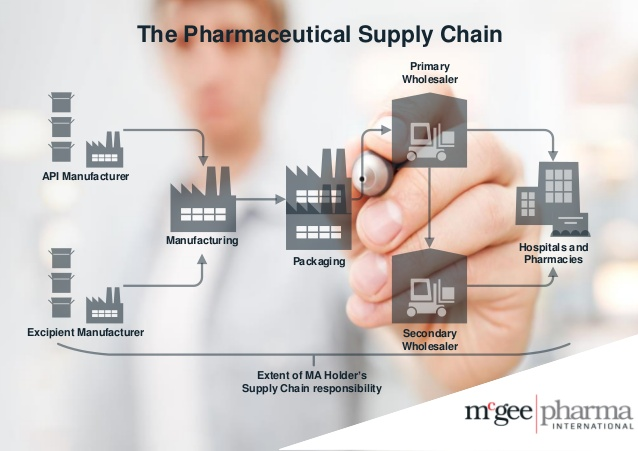

The complexity of pharmaceutical supply chains is growing exponentially. Prescription drugs are often just one aspect of the business as companies seek to offset shrinking margins by expanding into new areas: generics, over-the-er (OTC) products, health services, companion devices, and many other segments. At the same time, companies are using direct-to-consumer, direct-to-pharmacy, and other new distribution channels, and they are relying more on external partners for manufacturing, selling, and other services. The business is rapidly becoming more global, too. The result is a proliferation of plants, products, suppliers, trade channels, customers, demand pros, and service requirements—and minimal standardization of processes, procedures, and interfaces.

Despite these profound changes, few pharma companies have redesigned their supply chains. Instead, they’re using outdated models—ones that don’t meet today’s need for strategic segmentation. Because of this disconnect, the supply chain is still operating in a tactical manner instead of as a powerful competitive weapon.

.png)

EVOLVING CHALLENGES, COMPETING AGENDAS

The pharma industry has a unique set of challenges that has constrained past efforts to improve supply chains. For instance, quality standards can never be sacrificed in the pursuit of cost savings, and regulatory restrictions can inhibit some initiatives that could improve economies of scale. Moreover, to avoid the risk of running out of life-saving drugs, most pharma companies would rather err on the side of oversupply. But in today’s competitive business environment, companies must rethink the status quo and look for innovative ways to stay one step ahead—even if it means making tough decisions and profound changes. Pharma companies must capitalize on emerging markets, new distribution channels, and new areas of growth that demand cost efficiency and agility, such as generics, vaccines, and OTC products. At the same time, success requires an ability to guarantee the supply of targeted specialty-care and vaccine products to providers and patients.

To succeed, the pharma supply chain must be lean, low cost, and flexible—without sacrificing product quality and service. Unfortunately, the typical pharma supply chain—with its fundamental steps of purchasing, producing active pharmaceutical ingredients, manufacturing, and distribution—is subpar relative to that of other industries. It shows weaknesses in critical areas of performance, including cost of goods sold, overall equipment effectiveness, inventory turnover, and even service. Supply disruptions were prevented by investing heavily in inventory and production capacity—a costly approach but one that was justified by high product margins. With these preexisting constraints and inefficiencies, pharma supply chains are forced to be reactive at all times, and they can barely meet today’s business requirements without extraordinary effort. Companies that continue on this path will lose their ability to compete and are putting their future viability at risk.

BALANCING THE NEW PRIORITIES: SERVICE, COST EFFECTIVENESS, AND AGILITY

To meet the current industry challenges and increase overall competitiveness, pharma supply chains must improve how they manufacture and deliver finished goods, create new channel strategies, and drive revenue and margin performance. This ambitious agenda requires excelling in three critical dimensions:

Service. Supply chains must continue to ensure that the right products are at the right place at the right time. For some segments, this is the most important supply-chain priority, and cost effectiveness and agility are secondary considerations. When this is the case, pharma companies should design their supply chains to focus on product availability. An analysis of demand patterns will reveal which products have stable, predictable demand—and which have more volatile demand, possibly requiring investments in capacity and inventory. Once product availability is in place, companies can focus on offering greater speed, convenience, and other services to their customers.

Cost Effectiveness. Most pharma companies have already taken their supply chains down a long path of cost improvement, but success in some segments requires even lower upstream and downstream costs. For further savings, aim for standardized processes, lean techniques, faster inventory turnover, higher capacity utilization, and larger scale benefits.

Agility. Some segments require a highly responsive supply chain, one that can react quickly to changes in the business landscape. This agility can help pharma companies speed up product launches, extend the life cycle of existing products, enter new markets more quickly, and be more responsive to changes in demand and new business opportunities. Key features that lead to agility include effective planning and scheduling, rapid changeover of production lines, strategic use of inventory, production postponement, sourcing multiple suppliers, and external production capacity for greater flexibility.

PRIORITY-DRIVEN SEGMENTATION: FOUR MODELS

To manage these competing demands and the inevitable tradeoffs, pharma companies must determine their business priorities for each product and customer segment. They also need to create tailored supply-chain strategies on the basis of factors such as sales volume, demand volatility, product characteristics, life cycle maturity, customer needs, and competitive differentiation.

Using the three key business priorities of service, cost effectiveness, and agility, BCG identified four segmentation models that pharma companies can apply to their operations. The applicability of each supply-chain model depends on the business segment, customer needs, and key product behaviors and characteristics.

The Service Model.

This supply-chain model is well suited to segments in which the cost of an unavailable product is high, either due to reputational impact (in the case of medically necessary products), the availability of competing products, or basic economics if the product margins are high. Because aiming for 100 percent product availability is costly, the service model works best for high-margin products and those with predictable demand. The model requires investing in capacity and inventory to achieve high service levels. To get the highest return on these investments, pharma companies should optimize their production systems and inventory levels, capitalizing on demand predictability. Forward-looking companies are also rethinking traditional pharma products and their distribution and are looking for innovative service components that would be a source of competitive advantage and added revenues. For example, providing a ry’s ministry of health with an uninterrupted, temperature-controlled supply chain for vaccine distribution is a valuable service and makes demand more “sticky,” but it increases the complexity of the supply chain.

The Cost-Effective Model.

For segments with shrinking margins, inefficiency and waste must become relics of the past. Lean operations are critical when selling to emerging markets with significant pricing pressures, when competing against low-cost providers, and when selling lower-margin products such as generics and OTC drugs. The low-cost supply chain aims for manufacturing scale, high capacity utilization, streamlined processes, minimal complexity and waste, minimal transportation costs, and process reliability to keep costs low while maintaining high-quality standards. In many cases, these improvements require a step change in capability beyond what typical continuous-improvement programs will deliver. This model’s goals of maximizing capacity utilization and minimizing costs limit agility and make it necessary to allocate production across different markets and products. For example, manufacturers of generic products will pursue global scale, reduce product complexity, set up facilities in low-cost locations, and keep prices low, aiming for high volume rather than high margins. Generic companies must constantly rebalance their portfolios, adding new products and dropping those that no longer fit.

The Agile Service Model.

Availability and fast response times are critical when new products are launching, customer demand is volatile, and sales volumes fluctuate due to factors such as competitors moving in and out of a market and the introduction of competing drugs in a therapeutic area. The goal of the agility model is to create a flexible, highly responsive manufacturing and distribution network by rethinking current processes, production strategies, and network design; outsourcing noncore activities; and using partnerships, contract manufacturing, and logistics providers to increase flexibility. Strong end-to-end supply-and-demand planning and information flows are also critical in order to optimize inventory levels. Segments that will benefit the most this model are those in which product enhancements have resulted in a proliferation of stock-keeping units, new priority markets have highly uncertain forecasts, and constraints of a technical nature such as cold chain or shelf life require supply chains that are more flexible and responsive. A good example of a segment well suited to this model is a patented product with strong growth prospects in a large emerging market such as Brazil.

The Agile, Cost-Effective Model.

While high service and low cost tend to be mutually exclusive, agility and cost effectiveness can coexist to a certain degree in the same supply chain if companies thoroughly understand their business needs, plan rigorously, improve end-to-end processes, keep operations lean, and outsource noncore activities. They must also be ready to use partnerships, contract manufacturing, and logistics providers as needed to increase flexibility. This model requires ongoing communication between the business and supply chain operations through an effective sales and operations planning (S&OP) process. For instance, in competitive tender situations, demand can be hard to predict and downward pressure on prices means operations must be lean. To succeed, supply chain operations and the business must maintain an active dialogue to plan production and align priorities so that they can allocate product if supply is constrained. Moreover, the business must agree to accept potential product shortages in certain markets—a necessary tradeoff to allow for the coexistence of cost and agility. For example, after its key primary-care product lost patent exclusivity, one pharma company had to redesign its supply chain, moving a service model to a focus on cost effectiveness and agility in order to compete against generic manufacturers. The company consolidated its supply network, increased capacity utilization, minimized inventory levels, and redesigned production processes.

Cre: BCG